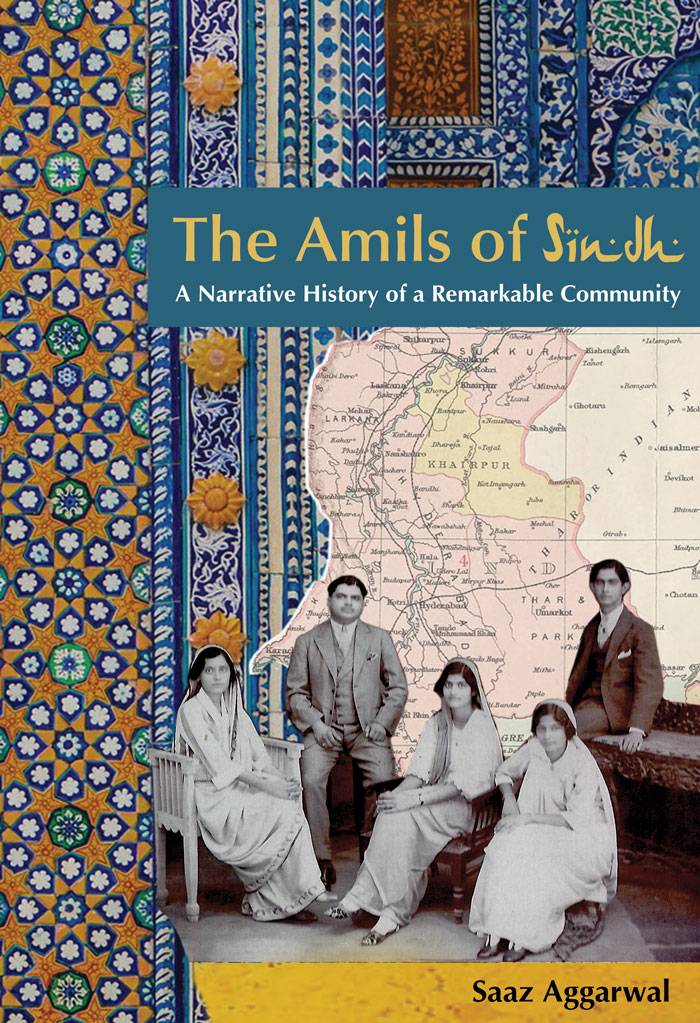

The Amils of Sindh

A Narrative History of a Remarkabe Community

Saaz Aggarwal

About The Amils of Sindh

The Amils of Sindh originated in a small group of families who migrated to Sindh through the seventeenth century, driven from neighbouring provinces by economic need, political forces and natural disasters. Through the centuries, the defining quality of the Amils was their commitment to education. They used their education to build careers for themselves, to lead comfortable lives and to create wealth for their families. As an elite layer of society, the Amils were inspiring role models and created a fervour of enthusiasm for education among the middle class in Sindh. The Partition of India and their subsequent dispersal cost them dearly, but they focussed on adapting with dignity to new lives in new places. This book honours the silent sacrifices of the generation that left so much behind. It provides the context for present and future generations to identify themselves with pride in family grids to which they belong.

VOLUME ONE is an introduction to this book with the style guide, a note on Amil surnames, comments on the complexities of restoring a lost legacy and acknowledgements.

This is followed by the history of the Amil migration into Sindh and their integration there, and how they established themselves in the courts of the indigenous princes of Sindh, first the Kalhoras and then the Talpur mirs. This volume provides information about why they began to be called Amils, and descriptions which evoke the environment in which the community came to be formed. It proceeds to describe how the new city of Hyderabad was built and populated. Clarifying that information about this period is rudimentary and often confused with later periods, it gives a view of the early days of Hyderabad and life for the Amils under Talpur rule. Some accounts that have endured, both historical as well as legendary, are presented here.

The British annexation of Sindh was a period of transition for the Amils. Great injustice was done to the Mirs but the Amils continued to be useful to the new rulers, and thrived. The British introduced infrastructure and systems, and included Sindh in the Bombay Presidency for easier administration. Here we get an insight into the changes this era brought to Hyderabad, the opportunities offered by the new capital Karachi and the rise of the Sindhworkis. The Amils immediately took to the new system of education, eagerly making their own initiatives to spread education across the province, with a strong focus on women’s education as well as on higher education.

There were Amils working systematically towards justice and self-determination even before the Indian National Congress did. There were also Amils responsible for law and order, and there are interesting stories which highlight the anomaly. Many ordinary Amils sacrificed their personal dreams to follow Gandhi, to create awareness about the exploitation of British rule, and to work for the upliftment of society. Ironically, with victory came the loss of their own homeland. This chapter commemorates the forgotten heroes.

Finally, this volume immerses the reader in Hyderabad, the capital city and home of the Amils, a place that would transform completely when they were forced to flee from it.

About Saaz Aggarwal

Saaz Aggarwal is a biographer, book critic, and humour columnist. With a Masters in Mathematics from Bombay University, Saaz Aggarwal taught early in her career at DG Ruparel College, Mumbai, and subsequently worked as HR head of Seacom, a retail software company in Pune. Saaz Aggarwal is also known for her Bombay Clichés — quirky paintings of contemporary urban India done in a traditional Indian folk style.

Praise for The Amils of Sindh

A valuable addition to Sindh studies, a new book presents the history and oral narratives of a community largely displaced during Partition,

Nandita Bhavnani, Dawn