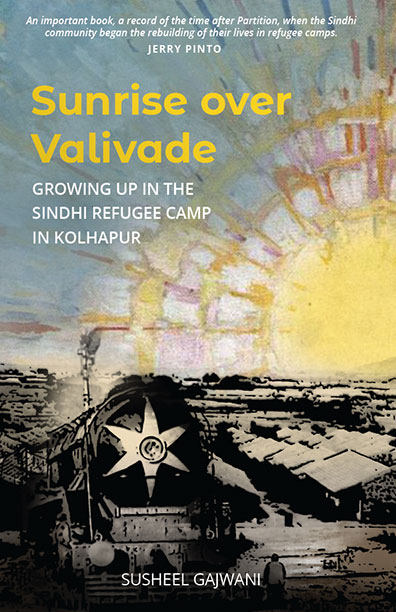

Sunrise over Valivade

Growing up in the Sindhi Refugee Camp in Kolhapur

Susheel Gajwani

About Sunrise over Valivade

This memoir, emerging from the well-populated yet little-known Gandhinagar Refugee Camp at Valiwade, Kolhapur, tells a story of heartbreak and devastation met with resilience and determination. It brings to light a history obscured by time, and the remarkable feats of ordinary men and women who adapted swiftly to their tragic loss and displacement, continuing to strive with all their might, to secure a better future for the generations that followed.

Poignancy weaves through this narrative, connecting rejection with reconciliation, loss of cultural heritage with relentless efforts to rebuild lives of comfort and dignity, and the past with the present.

Sindhis are seen all around the world – generally well settled and prosperous. Their presence is invariably taken for granted, their origins seldom considered, or understood, or even acknowledged. They are often reduced to shallow caricatures, moulded into a onedimensional monolith. Books like this allow the rich, multi-layered reality to emerge.

About the author

Susheel Gajwani is a writer, speaker and filmmaker, well-known for his columns, radio shows and performance poetry.

AakhreenTrain – The Last Train, his fourteenth feature film, is a Sindhi film based on the memoirs of well-known Sindhi writer Thakur Chawla, and put together by an inspired team including Shobha Lalchandani, Anil Chawla, Barkha Khushalani, Goldie Gajwani and Shashi Gajwani. It has been greatly appreciated in India, the US, and other countries where the Sindhi diaspora is spread.

His performance Roots – The Time Travellers is a musical based in Sindhi Partition poetry and its performances in English, Sindhi, Hindi, Punjabi and Marathi have been widely appreciated. It has evolved into Roots – a Million Dollar Confidence Musical, and continues to expand its horizons by including Partition poetry from around the world.

A Mumbai University double postgraduate in English Literature and Human Resources, and a Doordarshan Producer for seven years, Susheel Gajwani ran Money Satellite Television Channel as its Founder and Vice President. Money Television was India’s first Business Television Channel.

Susheel Gajwani played the high-performance role of lawyer-detective Bagu Barrister in the Sindhi feature film Anand Kripalani jo Murder, directed by renowned Sindhi author-filmmaker Bineeta Nagpal, and produced by Doordarshan.

A Rotary Foundation Technical Fellowship Recipient to study American media at New York University, Susheel Gajwani conducts life skills training workshops in Human Resources Development, Communication Skills, and Emotional Intelligence.

He continues to write on life skills and other topics in English, Hindi and Marathi newspapers.